After a PhD in technical physics, Ron Heeren started his career as a postdoc at AMOLF in 1993. Shortly after he established his own research group on macromolecular ion physics. Heeren has good memories of those times: "I recall regularly having a coffee with Jaap Kistemaker, founder of the FOM laboratory of mass spectrography and pioneer in the separation of isotopes. I would discuss the developments in mass spectrometry with him and he would say: ''No, that's impossible!' I would show him the results and he would then say: 'That's impressive, congratulations!' I thought that was fantastic!"

Developing new instruments

Mass spectrometry is a technique to identify molecules by analyzing their molecular weight. At the time when Heeren started, it was impossible to study intact marcomolecular ions. It was necessary to create fragments of molecules prior to their analysis and put the pieces of the puzzle together to obtain structural information of larger molecules.

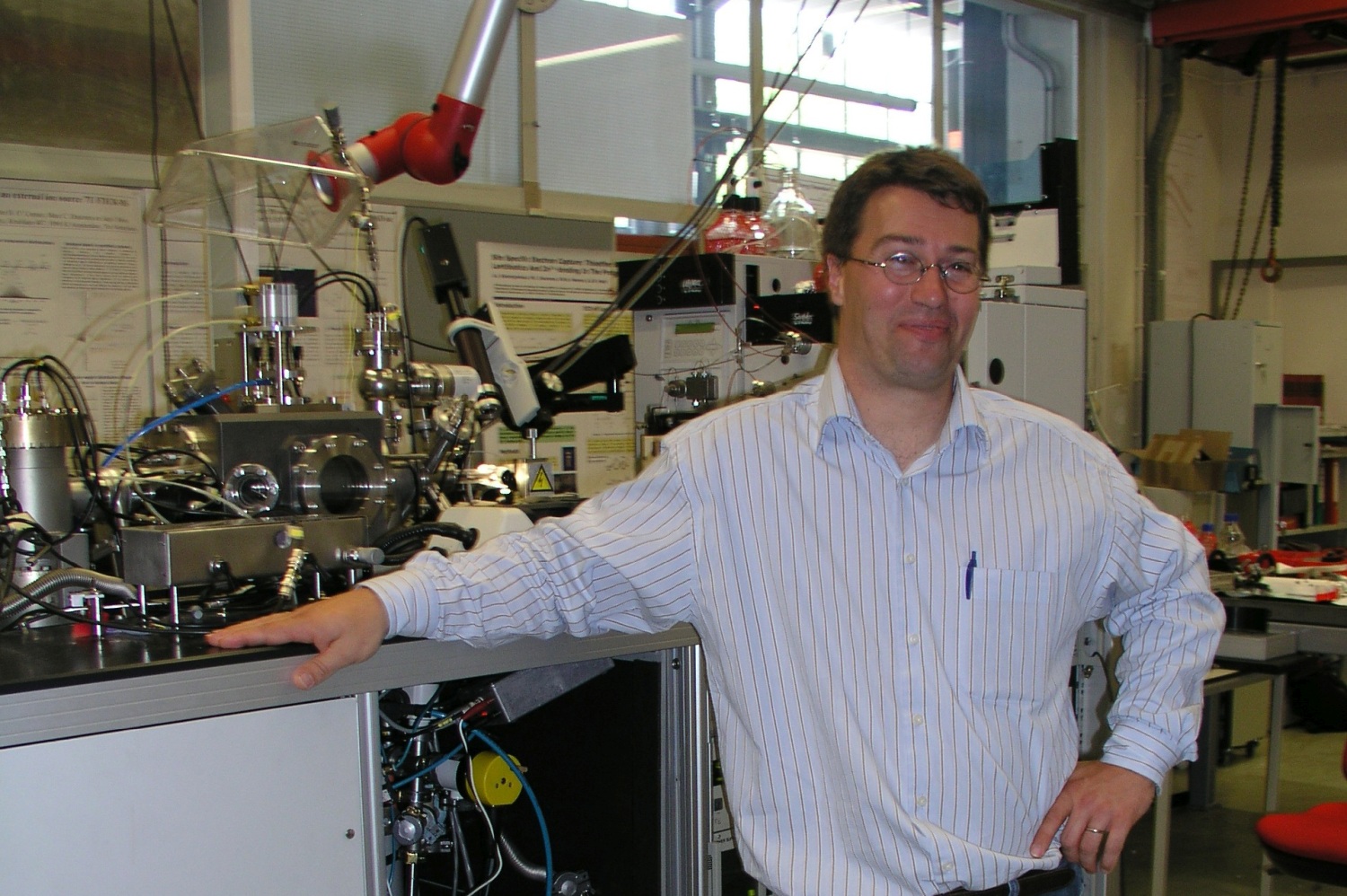

Heeren recalls: "A new Nobel-prize winning technique, electrospray ionisation, had just been developed with which we could ionise intact large molecules such as proteins and DNA. But the mass spectrometers in those days were not good enough to analyze these ions. Our task was therefore to build a new instrument that would enable intact macromolecular analysis."

With the new instrument, Heerens group was successful in analyzing the proteins. In the following years they built numerous new instruments and the focus of the group shifted to biomolecular imaging mass spectrometry. The colorful images that these instruments produce of samples like tissue or cells provide information on the spatial organization of the molecules on the sample surface.

"We developed fantastic instruments, we improved the resolution and increased the speed of the measurements. Many of the techniques we developed are now implemented in commercial instruments. Our group grew and our focus drifted from fundamental to applied biomedical research. My wish became to implement our knowledge in a clinical environment, which was difficult within AMOLF."

Move to a clinical environment

"What I appreciate in AMOLF is its role as an incubator," says Heeren. "Fundamental research and out-of-the-box ideas are nurtured and given space to grow. If they are successful and would benefit from further development outside the institute, this is encouraged."

"So it happened that I was asked to think about developing my ideas elsewhere around 2014. I wasn't sure, but what really convinced me to move was a meeting with a surgeon. He asked me to help analyzing isotopes relevant for a metabolic disease. We solved his issue within five minutes and that helped their patient research. Then I realized that by working in a clinical environment I could really make a difference. The young University of Maastricht was very accommodating and offered me a position. That was the start of the M4i institute where I am still the director."

The M4i (Maastricht MultiModal Molecular Imaging Institute) is one of the largest molecular imaging centres in Europe. The group now has 80 academic staff members and 45 high-end mass spectrometric instruments. Its focus is on a better integration of fundamental and clinical research. "In our office, the surgeon, pathologist, mathematician and MS specialist are neighbors. They casually learn from each other wich creates a new research dynamic that I really value."

High resolution images

A particularly successful development within the institute is the mass microscope, says Heeren. "The idea for this technique has been funded around 2000. But at the time the technical challenges were too big: detectors and software were not fast enough for the huge amount of data it produced. This could be up to a terabyte per minute."

Just two years ago using a modified version of the first instrument, the mass microscope flourished. Conventional imaging mass spectrometers produce images by scanning dot after dot of a sample, 40 to 1000 dots per second. The smaller the dots, the higher the resolution of the image but the longer the measurement takes. A pathologist needs an analysis of an entire biopsy for example of a tumor. Scanning a sample of this size would take a year with the old apparatus.

Heeren: "Using the new instrument we can scan one million pixels per second and obtain the result in minutes. The results allow the pathologist to identify the cell type, see if it is active or distinguish between a malignant or benign tumor. That information helps clinician to tailor a better treatment for the patient."

The next step is the ability to image a living, dynamic environment. At present, the samples are frozen and static. "Imaging dynamic samples is now only possible by labeling molecules for example with a fluorescent probe and an optical microscope. We are working on a mass spectrometry imaging technique for dynamic samples that do not require labeling."

Aging paintings

Recently, Heeren re-entered an entirely different field of application of imaging mass spectrometry: studying the molecular composition of art. At the start of his AMOLF-career, he was involved in the research program MolArt which studied the molecular aspects of aging of art using mass spectrometry together with Jaap Boon. "We did a successful analysis of Rembrandt’s 'Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp' which I still use as an example in lectures. Jaap Boon taught me to think across the boundaries of disciplines and develop a biological and application-oriented view. He was the prototype 'homo universalis', I owe to him my passion for interdisciplinary research." Boon recently passed away and Heeren says that meeting old colleagues at the ceremony was the start of several new projects in the field of molecular aspects of art.

Heeren has always valued the sense of togetherness within AMOLF."We were pioneers and the institute always stimulated out-of-the-box thinking. This freedom and the dynamic and interdisciplinary ecosystem is present in Maastricht as well. That is why I feel so much at home there. The surgeon I work with is in the office next to me and sometimes we go cycling together through the Limburg hills. Feeling at home at work is a crucial element for a successful scientific career."