Cathepsins play a role in all stages of cancer varying widely from immune cell regulation to matrix degradation. Inhibiting cathepsins with small molecules is a promising target for cancer treatment, but cathepsins are not only functional in tumor cells but also in virtually all normal cells. Specific functions of each cathepsin are becoming increasingly evident. Cathepsin B and L for example are present in virtually all cells, while S and K are mainly found in antigen presenting cells and osteoclasts, respectively.

Inhibiting systemic cathepsin activity can therefore be harmful in many ways. Targeting cathepsin activity must be done more selectively, which EPFL researchers in Lausanne (Switzerland) with help from the Chemical Immunology Lab of Martijn Verdoes at Radboudumc in Nijmegen set out to achieve.

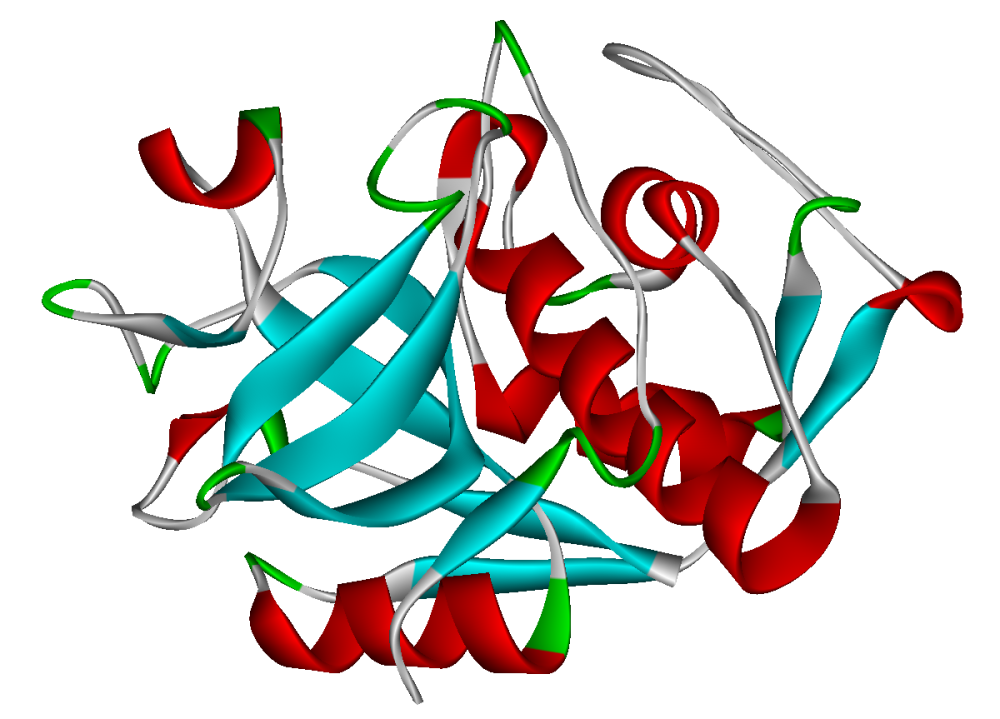

The Swiss researchers led by Elisa Oricchio and Bruno Correia at EPFL first developed a platform to rapidly screen candidate peptide inhibitors (non-natural peptide inhibitors, NNPI). This resulted in some very potent and specific cathepsin inhibitors. "The result is remarkable," says Verdoes. "The approach has produced a new class of inhibitors which are very selective and the binding mechanism has been proven by modeling and crystal structure analysis as well."

Targeted inhibition

The next step was testing the most potent inhibitors on a biologically relevant system. Verdoes is a specialist in developing tools for this, he explains: "In a biological environment many cathepsins are present at the same time. We developed a tool to investigate the biological activity of the inhibitors in a cell or organism, a so-called quenched activity-based probe (qABP)." These probes are reporters of cathepsin activity. The probe is fluorescent only after reacting with a cathepsin. Indeed, in all of the studied cases, adding an inhibitor prevented the binding of the probe to the specific cathepsin and the fluorescence disappeared.

Then, the researchers developed a way to bring the inhibitor to the targeted tumor. They created an antibody-peptide inhibitor conjugate (APIC) which effectively traps a specific cathepsin in a specific cell type. The non-targeted inhibitor is hardly active, reducing the risk of side-effects.

To prove the efficacy of the APIC, a lymphoma was chosen as the target using an anti-CD79 antibody and the cathepsin S inhibitor NNPI-C10. Verdoes explains: "This type of lymphoma needs cathepsin to grow and proliferate, but it also uses cathepsin to enhance the activity of helper T-cells that stimulate growth of the tumor cell. In addition, inhibiting cathepsin activity stimulates cytotoxic T-cells." The researchers showed that the approach works for other tumor cells such as breast cancer cells and osteoclasts as well, proving the wide applicability.

On the way to clinical trials

Finally, this targeted delivery of potent cathepsin inhibitors was tested in vivo in mice. The results are very promising, says Verdoes: "The inhibitors were shown to be very active and were delivered exactly where they need to be. In the case of lymphoma not only the therapeutic molecule was identified but also the mechanism. That is very important for the translation to cancer treatment. The next step now is additional in vivo studies and then phase 1 clinical trials."

Petruzzella, A., Bruand, M., Santamaria-Martínez, A. et al. "Antibody–peptide conjugates deliver covalent inhibitors blocking oncogenic cathepsins." Nat Chem Biol 20, 1188–1198 (2024).